An AI vision company is launching a wearable camera for tracking your relationships. If that sounds creepy… well, it sort of is. And if it sounds useful, it might be that, too. It’s a device that seems almost custom-built to tap into our fears about how technology will change relationships. And it almost certainly won’t be the last of its kind.

The product is called the OrCam MyMe, with an expected launch in March 2019. OrCam co-founder Amnon Shashua describes the MyMe as a “

The MyMe is a thumb-sized black plastic rod with a wide-angle camera embedded into it. (The first Kickstarter backers can buy it for $199. After that, it will sell for $399.) Clip it to your chest and pair it with a phone, and it takes a picture once every second. If there’s a face in the picture, it cross-references that face with your social media contacts or previous MyMe photos. Once it knows who you’re meeting with, their name will pop up on your phone. And after enough use, it’s supposed to quantify your relationships — with friends, co-workers, and humans in general.

The MyMe hardware evokes lifelogging cameras like the Narrative Clip, which were briefly popular in the early 2010s, and its software evokes NameTag, a facial recognition app built for Google Glass in 2014. But lifelogging produced reams of mostly useless footage, and Glass was maligned as invasive and creepy. Shashua thinks MyMe can succeed where both failed — mostly because it’s offering a service that goes beyond novelty.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/13616006/arobertson_181204_3132_7898.jpg)

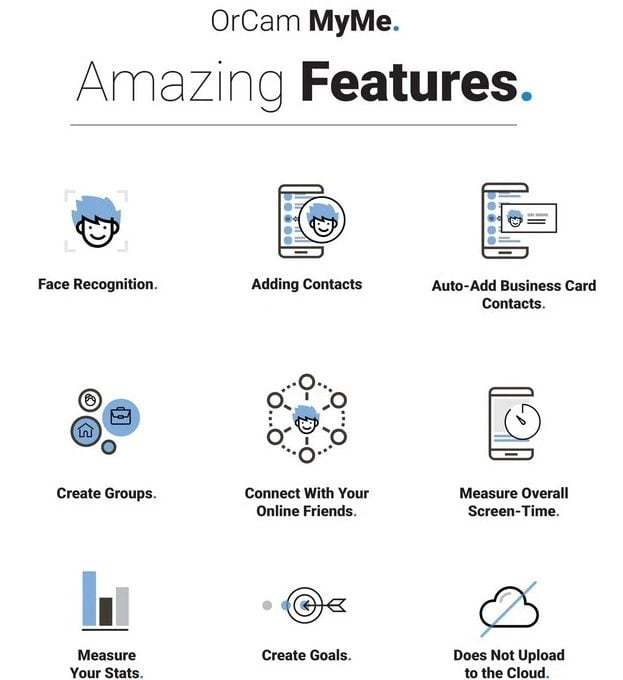

The camera’s core function is matching faces with names. (In addition to social media and manual tagging, it’s supposed to pull names off conference nametags and business cards.) Its software will also let you tag people into groups, add notes about your conversation, or see their latest social media post. Using this data, the MyMe is supposed to analyze the amount of time you spend with specific groups or individuals. It can theoretically note that you’re spending far more time with colleagues than with friends or family, for instance, or if you’re working on a group project, that you haven’t seen a specific team member in a while.

More broadly, the MyMe is supposed to track how much time you spend looking at people versus, say, screens. (If your screen is showing a face, the camera will apparently still count that as facetime, since it isn’t built to gauge depth.) “You measure steps in order to kind of quantify your physical health,” says Shashua. “What about social bonding?” The MyMe could let you set weekly goals for how much time you want to spend with “significant” people in your life, for instance. And like a fitness tracker, it would chide you for missing that benchmark, so you’ll work to hang out with them more the next week.

OrCam is trying to head off privacy questions by keeping all the photos strictly on the camera or your phone, rather than syncing them with a cloud service. It doesn’t save images, unless it spots a new person, in which case it saves a thumbnail for you to review and tag. It’s also not claiming to build any kind of universal face recognition database; it’s more like a personal address book.

But whether or not the MyMe seems invasive, it violates basic norms about social interaction. Wearing one implies that remembering people is too much work and interacting with them is a chore. It could earn the kind of backlash that greeted Romantimatic, an app that reminded people to text nice things to their partners. (One critic argued that “if you need this app you’ve failed as a human being.”) When you meet up with a friend, will they believe you really want to see them, or will they worry that you’re just gaming your

Shashua points out that people make those trade-offs all the time elsewhere: GPS navigation has largely replaced maps, and cellphones made memorizing phone numbers unnecessary. Many people already outsource their birthday greetings to Facebook, although not without some consternation. And have people ever really believed that all social interactions are voluntary and enthusiastic?

Of course, all of these questions are moot if the MyMe doesn’t work as advertised. OrCam is an established company, and Shashua is also the CEO of Intel-owned computer vision firm Mobileye; the MyMe is essentially a product that people can preorder on Kickstarter, not a gadget whose quality depends on crowdfunding money. In an extremely limited test, Shashua’s wearable camera took a picture of my face, then identified me correctly later. It looks most natural (relatively speaking) when clipped onto a button-down shirt, but I could pin it to my blouse fairly easily with a magnet, too. That doesn’t amount to much of a stress test, unfortunately.

No matter how many people buy the MyMe, though, this seems like inevitable territory for Apple, Google, Facebook, or Amazon to stake out. All these companies have invested in facial recognition and consumer augmented reality, and Google has actually released its own miniature camera called Clips, which uses AI to detect people you know and automatically film them. If a major tech company released smart glasses that copied the MyMe, the implications would become more clearly dystopian: imagine Facebook estimating the strength of your marriage and serving counseling ads, or Apple clumsily micromanaging your friendships the way it manages your health.

Shashua says that “of course” the

By Adi Robertson